|

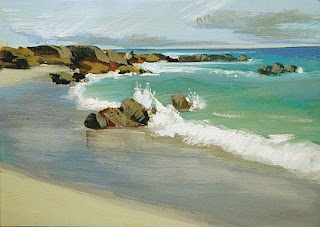

| "Island Sea" |

I’m no specialist in seascapes, since I've lived in New Mexico for 30 years, but I grew up on the beaches of California and spent a lot of time looking at the sand, cliffs, water and waves. This class is thus a survey of a few things to pay attention to as you paint the beach and ocean, not a specific inquiry into each element, which would require far more study.

Obviously we’ll be working from photographs, so let’s start with a good candidate for your painting. The shot of the beach and wave looking straight out to sea (A) can be boring, creating horizontal stripes that require a lot of creative widths to be very interesting. That’s actually a more challenging composition than you think. Too often it’s static, so if you choose this composition, carefully vary the widths of each band of color and be certain no line rests on the horizontal center line.

|

| A |

|

| B |

Instead a slight angle looking up or down the beach (B and D), including some of the sea, can often be more inspiring and interesting to paint. If there are cliffs or rocks, waves or splashes, wet sand or foam, you have many more opportunities for a compelling and vibrant scene.

| ||||||

| C |

|

| D |

No matter what, you should analyze the view and look for any tangents, such as the rock that‘s just kissing the horizon line in D. Push that rock up slightly, or drop it significantly under the horizon to create a sense of depth in different ways.

It might also be advisable to rotate your photo so that any horizon line is level as you paint it (D.) The ocean doesn’t slope sideways but a photo can make it appear that way. Establish a straight and level line of the visible horizon on your paper. Rulers are great tools invented for this purpose.

|

Let’s look at the sandy beach. I find it advisable to establish the local color of the sand, including sand wet by the incoming tide. Keep in mind that all beaches slope down toward the water, whether steeply inclined or not. Notice that you can see the sand color beneath the water in the shallows. Depending on the medium you’re using you might lay this color in first and layer over it, but no matter the procedure keep this sand color in mind as you paint. Wet sand is slightly darker and reflective. Add darks first, establishing the color of the wet sand as containing the dry sand color in a darker value, and then add light sky colors over the top.

Add footprints last, often made up of a rim of lighter sand color on one edge and shadowy colors beside it.

Beach rocks can be interesting and compelling elements in the composition. All of the rules for rocks need to be observed (planes, planes, planes!) However, these rocks are softened by wave action. Paint them with planes that have softened edges, paying attention to the characteristic fractures or holes.

Cliffs along the beach will also add recession to a painting. Use more contrast and stronger, more saturated colors in the foreground, progressively using bluer and paler colors in the distance.

Look for sets of waves, although the intervals and interrelationships of these sets is widely variable. Notice they all enter the beach from the same direction, usually following the beach line, but affected by any rocky outcroppings, manmade breaks, or a shallow or steeply inclined bay.

A wave is a complex shape. The water is moving due to its own energy, the contours of the sand and rocks beneath it, and whether or not there is a swell in front of it impeding its travel or behind it pushing it on. Keep all the lines of a wave rounded and fluid, no matter how hard-edged they are. Simplify the contours to see the relationships, defined by the values. Paint the colors beneath these shapes and add lighter colors as you progress, as well as reserving details for last.

The curl of a wave has a foamy splash where it lands on top of itself, and sea foam describes swells, cross-currents, back washes, and breakwaters. Oftentimes the brightest light in view is not this foam but sparkling reflections where sunlight dazzles. Notice in the photo below where the strongest lights are located, in opposition to the direction of the sunlight.

There’s a small but sometimes key element to pay attention to as you paint an incoming wave that has flattened and now speeds its way up the beach in a gently curving arch, marked with foamy bits. Look for the shadow you will often see along its edge there. It isn’t a hard line, and its edges fluctuate like a ribbon, helping to make the wave seem fluid and lively.

Simplify the wet sand if the foam patterns are too complex to portray well. For instance, in the photo above you might make the arc of wet sand lavender, forgetting the foam there (yellow arrow.) Look for the color of the sand influencing the wave color, progressively growing darker as the water deepens, and use foam patterns to suggest water movement.

Is the color of the ocean darker near the horizon or lighter?

There is no hard and fast rule regarding this. It depends on the angle of the light, the conditions of the sky and the relative height from which you’re viewing things. I suggest you rely on your photograph to give you needed evidence of water color and value. However, I often find that the horizon line can become so blurry as to be nonexistent in some photos. I usually choose to show it somewhat more clearly in at least one location, which I find gives the viewer a solid sense of distance.

Let me share a few of my gouache paintings with you, each of which is 2.5" x 3.5" in size, on various kinds of paper:

|

| "Sparkle" |

|

| "Sandy Shore" |

|

| "Sentinels" |

|

| "High Tide" |

|

| "Summer Bay" |

|

| "Wet Sand" |